I. Why healthcare stands out in India’s investment ecosystem

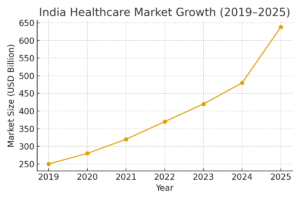

India’s healthcare sector has emerged as an attractive destination for deployment of capital by marquee private equity and venture capital funds in recent years. 1 It has received attention from both global and domestic investors looking to capitalise on the growth potential of the sector, banking on increasing public health awareness, consistent demand for accessible and quality healthcare facilities and rising government health expenditure. The strong appeal of the sector is evidenced by the infusion of nearly USD 14.5 billion of invested capital in the period between 2020 to 2024, with 58% of the capital inflows coming in during the years 2023 and 2024. 2 Investor focus appears to be concentrated on opportunities in the hospital segment, 3 supported by optimistic projections estimating the aggregate market value of Indian hospitals to surge to nearly USD 193 billion by 2032. 4

The Indian healthcare sector’s growth trajectory has been bolstered by its solid fundamentals. With healthcare being an essential service, valuations in the sector remain relatively shielded from broader macro-economic fluctuations, offering investors visibility on long-term returns. Supportive government policies and increased public spending have further strengthened the investment outlook in the sector Allocations towards the Department of Health and Family Welfare totalled to INR 95,957.87 crore (around USD 11.07 billion) in the Union Budget for FY 2025–26. 5 India is also positioned to benefit from its reputation as a leading medical tourism destination, with the value attributable to medical tourism estimated to exceed USD 13 billion by 2026. 6

Undeterred by shifting population dynamics, the demand for essential healthcare services, including critical care, pharmaceuticals and diagnostics, has remained fairly resilient. 7 At the same time, with the rise of lifestyle disorders, preventive healthcare has become the need of the hour. 8 This has spurred a rise in health-tech investments,9 with digital health solutions creating fresh investment opportunities in areas such as telemedicine 10 and single speciality disease management platforms. 11 These technological advancements, supported by favourable demographics, are transforming the delivery and financing of healthcare in India. This evolution of the Indian healthcare sector is unfolding within a highly complex legal and regulatory environment.

II. Foreign investment in healthcare

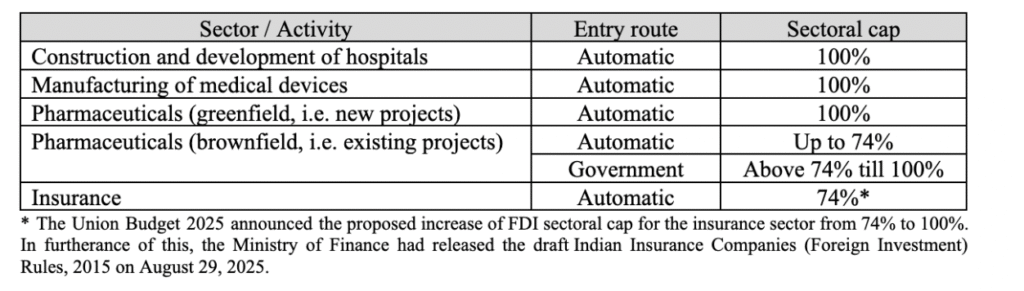

The potential of the Indian healthcare sector is evidenced by the rise in foreign direct investment inflows. In the financial year 2023-2024, the healthcare sector received foreign direct investment amounting to USD 1.5 billion, with an estimated 50% of the inflows being parked in target companies in the hospital segment. 12 India’s foreign investment regime provides sufficient headroom for foreign investment into the healthcare sector.

The relevant entry routes under the Foreign Exchange Management (Non-Debt Instruments) Rules, 2019 pertaining to the healthcare sector are set out below.

A substantial portion of foreign investment in the healthcare sector, particularly in relation to manufacturing of surgical devices, diagnostic equipment, and therapeutic devices, has been contributed by foreign venture capital investors (“FVCIs”), 13 entities registered under the SEBI (Foreign Venture Capital Investor) Regulations, 2000. FVCIs are generally permitted to invest in the securities of unlisted Indian companies operating in specified sectors, 14 including inter alia (a) biotechnology, (b) research and development of new chemical entities in pharmaceutical sector, and (c) infrastructure (hospitals (capital stock), medical colleges, para medical training institutes and diagnostics centres). 15 However, this sectoral limitation is not applicable to FVCIs investing in equity instruments or debt instruments of recognised Indian startup companies, although the terms in relation to entry route, sectoral caps and conditions will continue to apply in case the investment in such startup is through equity instruments. 16 This regulatory flexibility has made foreign venture capital funding a viable source of funding for new-age healthcare startups.

III. Healthcare governance: Navigating central and state jurisdictions

Healthcare is a highly regulated and scrutinised sector in India. The constitutional impetus for the legal regime governing healthcare in India comes from Article 47 of the Constitution of India, which is a directive principle of state policy providing that the State should view the improvement of public health, raising the standard of living of the Indian population, and enhancement of their nutrition levels as one of its foremost duties.

In line with the federal structure of governance, various matters pertaining to healthcare have been delegated to the states pursuant to the State List, including public health, sanitation, hospitals and dispensaries, rendering states as the principal authorities for healthcare related governance.17However, the presence of subject matters such as medical education, population control, family planning, regulation of medical and allied professions and drugs form part of the Concurrent List. 18 This results in the existence of a dual and fragmented model of governance in India, whereby both central and state laws regulate aspects of healthcare delivery.

The fragmentation in the regulatory framework is discernible from the varying laws governing clinical establishments in the country. The Clinical Establishments (Registration and Regulation) Act, 2010 (“CE Act”), a central legislation, has been formally adopted by only select states and union territories, with the remaining states choosing to pass state-specific regulations to govern the same subject matter. For example, the states of Karnataka, Maharashtra, West Bengal and the union territory of Delhi have their own legislations governing nursing homes and hospitals, which differ from the CE Act in terms of the compliance requirements.

Accordingly, healthcare providers operating across different states or on a pan-India basis are required to be cognisant of and compliant with a whole host of cross-jurisdictional legal requirements governing their legal existence and operations.

Further, India’s regulatory ecosystem requires healthcare providers to routinely engage with various sectoral regulators such as the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation, the National Health Authority and the National Medical Commission, which play the primary role in devising and implementing Indian healthcare policy, and maintenance of healthcare standards. At the same time, periodic interactions with statutory bodies such as the Pharmacy Council of India, the Dental Council of India, the National Nursing and Midwifery Commission and the Medical Council of India also remain important, considering the roles of these bodies in standard-setting for medical practice and credentialing of healthcare professionals in India. Constant liaising by healthcare providers with both central and state-level agencies is crucial to ensuring their operational viability.

IV. Regulatory framework for healthcare facilities

Given the multiplicity of laws governing them, entities engaged in the provision of healthcare facilities should periodically check for region-wise legal developments and procedural changes, to ensure that their business remains legally compliant in all respects. Correspondingly, financial investors looking to invest in the healthcare sector must undertake comprehensive jurisdictional due diligence to ensure that their target companies operating in the healthcare sector are adhering to the provisions of applicable laws and have consistently maintained necessary licenses and permits during the entire duration of their operations. Few of the key regulatory compliances which may apply to a healthcare establishment are summarised below.

A. Establishment of a clinical establishment

Registration, either under the CE Act or the state specific clinical establishment law (depending on the place of the establishment) remains a prerequisite for establishing healthcare facilities in India. The laws governing this space provide a broad definition for the terms ‘clinical establishment’ and/or ‘nursing home’, with a view to bringing maximum number of healthcare facility providers within regulatory purview. However, there are also instances of difference in the scope of applicability in these laws. For instance, the definition of ‘clinical establishment’ under the CE Act mentions hospitals, maternity homes, dispensaries, nursing homes and clinics, whether owned, controlled or managed by a corporation, a single doctor, a trust or the government. 19 Although the term is similarly defined under the West Bengal Clinical Establishments (Registration, Regulation and Transparency) Act, 2017, the legislation does not apply to any clinical establishment under government control. 20

Registration timelines too remain inconsistent across different states. The CE Act authorises states which have adopted it to issue provisional registrations for a period between 6 months to 2 years (depending on status of the notification of applicable standards by the central government) and permanent registrations for a period of 5 years. 21 The Maharashtra Nursing Homes Registration Act, 1949 and the Delhi Nursing Homes Registration Act, 1953, on the other hand, provide that registrations shall be valid until March 31 of the third year since the date of issue of the original or renewed certificate.22

B. Providing specialized medical offerings

Apart from the general registration which allows for the establishment and operation of a healthcare facility, various special licenses may be required depending on the nature of medical procedures and/or services which are sought to be offered.

(i) Compliances for reproductive and fertility clinics

The setting up and operation of assisted reproductive technologies (“ART”) clinics and ART banks in India is regulated under the Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Act, 2021 (“ART Act”) and the Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Rules, 2022. ART is an umbrella term referring to technological solutions which allow single women and infertile couples to conceive a child. The ART Act and the rules thereunder are designed to ensure that ART services, including in vitro fertilisation (“IVF”), intrauterine insemination and embryo transfers, are made available in a safe and ethical manner.

Registration under the ART Act is mandatory for any organization seeking to offer ART services. The registration is for an initial period of 5 years, which is renewable for a further period of 5 years at a time. 23 The registration is non-transferable in nature. In case of any change in the ownership or management of a registered ART clinic or ART bank, the existing registration is required to be surrendered, and the new owner is required to apply for a fresh registration.24

The ART Act enables both infertile married couples as well as unmarried women aged above 21 years to seek ART services from authorised clinics. 25 ART services are permitted to be provided to women and men who are less 50 years and 55 years in age respectively. 26 To ensure safety of all parties involved, the ART Act and the corresponding rules set out the particulars regarding the nature of physical infrastructure and equipment requirements and staff qualifications for ART clinics and banks. 27 ART clinics are required to obtain written and informed consent from the parties seeking ART services, 28 provided that such consent is capable of being withdrawn at any time prior to the transfer of embryos or gametes to the uterus of the concerned woman. 29 Further, prior to performing any ART treatment or procedure, ART clinics are required to ensure that the commissioning couple or women have obtained an insurance policy from an insurer or agent which is recognised by the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority (“IRDA”). 30

Pursuant to the terms of the ART Act, gametes and embryos are allowed to be stored for a maximum period of 10 years, post which such gamete or embryo must either be allowed to perish or be donated to a registered research organisation with the consent of the commissioning couple or woman, as the case may be. 31 Provision of any ART service for ensuring or increasing the probability of a child of a specific sex being born or any advertisement of services of such nature is strictly prohibited. 32

(ii) Surrogacy clinic registration

Facilities offering surrogacy services are governed by the Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021 (“Surrogacy Act”) and the Surrogacy (Regulation) Rules, 2022. The Surrogacy Act provides for registration of surrogacy clinics and facilities providing surrogacy procedures. 33 The legislation permits only altruistic surrogacy where the intending couple or the intending woman has a medical condition which requires gestational surrogacy, and explicitly prohibits any form of commercial surrogacy. 34 It contains a deeming fiction pursuant to which a child who is born out of surrogacy is deemed to be the biological child of the intending couple/woman and is entitled to all rights which would otherwise have been available to a naturally conceived child. 35

The Surrogacy Act contains several provisions to ensure ethical medical practices and to protect the rights of surrogate mothers, including inter alia the right of the surrogate mother to withdraw her consent prior to implantation of the embryo in her womb, 36 prohibition on the abandonment of a child born out of surrogacy 37 and restrictions on the act of compelling the surrogate mother to undergo abortion, other than in accordance with the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971 (“MTP Act”). 38 Further, having regard to the health of the surrogate mother, gynaecologists are permitted to transfer only 1 embryo in the womb of a surrogate mother during a treatment cycle under general circumstances, with transfer of up to 3 embryos being permitted only in special circumstances. 39

Further no more than 3 attempts of a surrogacy procedure is permitted in relation to a surrogate mother. 40

In relation to the expenses which may be incurred by the surrogate mother, the Surrogacy Act mandates that the intending couple/woman should maintain a general health insurance policy from an IRDA recognised insurer or agent, providing coverage to the surrogate mother for 36 months for such amount which shall be adequate to cover expenses arising from pregnancy complications as well as post-partum delivery complications. 41 The intending couple/woman is also required to provide a sworn affidavit before a metropolitan magistrate, first class judicial magistrate, executive magistrate or notary public guaranteeing to provide compensation for medical expenses, health issues, specified loss, damage, illness or death of the surrogate mother. 42

(iii) Registration of genetic and prenatal diagnostic centres

The operation of clinics, medical institutions, hospitals, nursing homes, laboratories and other facilities in India engaged in providing genetic counselling, prenatal diagnostic procedures and related imaging or analysing samples from such procedures is governed by the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection) Act, 1994 (“PCPNDT Act”) and the Pre- conception and Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection) Rules, 1996 (“PCPNDT Rules”). The PCPNDT Act specifically prohibits the carrying out of any procedure for ensuring or increasing the probability of a child of a specific sex. 43 It also prohibits the sale of any equipment such as ultrasound machine / imaging machine which can be used for pre-natal sex determination to any medical institution which is not registered under the PCPNDT Act. 44

Medical establishments can obtain registrations under the PCPNDT Act for periods of 5 years at a time, subject to renewal by the appropriate authority in the relevant state / union territory. 45 The PCPNDT Rules further specify the minimum requirements regarding equipment and staff qualifications which registered establishments must follow.46 In case of change of employees, place and address of operations or the nature of equipment used, registered establishments are required to intimate the appropriate authorities under the PCPNDT Act within 30 days of the occurrence of the change. 47 Apart from registration, medical establishments undertaking pre-natal diagnostic tests are required to adhere to standards relating to record-keeping and consent management, as well as the code of conduct prescribed under the PCPNDT Act.

(iv) Legal norms governing termination of pregnancy

The MTP Act and the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Rules, 2003 govern the operations of abortion clinics in India, permitting abortions to take place only in government hospitals and such private medical institutions which are approved by committees constituted under the MTP Act. 48 With a view to ensuring that abortions are undertaken in a safe and hygienic manner, the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Rules, 2003, sets out the mandatory facilities which need to be maintained by a medical establishment providing the service of termination of pregnancy.49

Given the sensitivities involved, the permitted time period till which a pregnancy can be terminated has been the subject of extensive contention in Indian legal circles. 50 Currently, abortions are allowed up to 20 weeks of gestation under general circumstances. Termination of pregnancies up to 24 weeks is also permitted but in very specific cases, 51 provided that even in such special circumstances, at least 2 registered medical practitioners need to certify that continuing the pregnancy would result in a risk to the life of the pregnant woman, grave injury to her physical/ mental health or would cause physical/mental abnormality in the child who is born. 52

(v) Accreditation of organ and tissue transplantation centers

The Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Act, 1994 (“THOTA”) and the Transplantation Rules, 2014 is meant to govern the conduct of organ and tissue removal, storage, and transplantation across India, apart from the state of Andhra Pradesh which has its own law in this regard. 53THOTA provides for the registration of hospitals, human organ retrieval centers and tissue banks 54 undertaking the removal of organs/tissues and transplantation thereof, for a period of 5 years at a time. It prohibits the removal or transplantation for any reason other than therapeutic purposes and criminalises commercial dealings in human organs or tissues. 55

THOTA allows for removal of human organs and tissues from deceased persons and persons who have suffered brain stem death, subject to receipt of authorisation in the prescribed manner, either from the deceased person prior to his death or the person who is lawfully in possession of the dead body of an individual, as the case may be. 56 It also permits persons in charge of hospitals or prisons to provide authorisation for the removal of organs and/or tissues from an unclaimed body of a deceased person which is not claimed by their near relatives within 48 hours from the time of death. 57

THOTA seeks to build in sufficient checks and balances in the organ donation process so as to prevent exploitation of vulnerable persons. For instance, it provides that as a general rule, organ or tissue which is removed from a donor shall be transplanted into a recipient who is a near relative of the donor. 58 However, the donor may prior to his death authorise the transplantation of his organs to a recipient who is not his near relative on account of his affection or attachment or other special reasons, provided that in such case the removal and transplantation of the organs and/or tissue shall be subject to approval of an authorisation committee constituted under THOTA.59

(vi) Regulation of blood banks and stem cell facilities

Healthcare establishments involved in the collection, testing, processing, storage, or distribution of human blood or umbilical cord blood stem cells fall within the purview of Chapter XB of the Drugs Rules, 1945. Subject to their compliance with the prescribed conditions regarding technical staff, space and equipment, blood banks and facilities processing components or products of blood may be granted licenses for operations for a duration of 5 years at a time.

(vii) Permissions for radiation-based medical infrastructure

Facilities operating radiation-generating equipment, such as X-ray machines or CT scanners, fall within the scope of the Atomic Energy Act, 1962 and the Atomic Energy (Radiation Protection) Rules, 2004. Accordingly, hospitals, clinics and diagnostic centres utilising medical equipment such as computed tomography (CT) units, interventional radiological x-ray units, medical diagnostic x-ray equipment and nuclear medicine facilities, 60 are required to obtain licenses from the Atomic Energy Regulatory Board which are valid for a period of 5 years at a time. 61

V. Technical and operational compliance for healthcare establishments

In addition to the specific licenses pertaining to the medical equipment used and the services which are rendered by medical establishments, they may also be required to secure and maintain applicable non-medical licenses. These may include, but not be limited to:

Electricity permits and approval / no objection for diesel generator sets pursuant to the Electricity Act, 2003;

No objection certificate from state fire departments pursuant to state-specific fire safety laws;

Registration for lifts pursuant to state-specific lift laws;

Trade licence from municipal authorities;

Licence for possession of rectified spirit including absolute alcohol for medical use pursuant to state excise laws;

Licence pursuant to the Gas Cylinder Rules, 2016 in case more than 200 cylinders of a non- toxic gas (such as oxygen) is being stored; and

Licence to sell drugs pursuant to the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1945 in case of an in-house pharmacy.

VI. Voluntary Accreditation and Quality Assurance

While not legally mandated, obtaining voluntary accreditation from industry wide standard-setting bodies is increasingly being viewed as a hallmark of institutional quality for healthcare institutions. The National Accreditation Board for Hospitals and Healthcare Providers (“NABH”) and the National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration Laboratories (“NABL”) are the two principal bodies offering certifications for healthcare institutions in India. NABH focuses on hospitals, clinics, laboratories, and traditional medicine centres and outlines patient-centric and operational quality benchmarks, including in relation to quality management and patient safety. On the other hand, NABL focuses on certifying diagnostic and testing laboratories which adhere to international standards in terms of analytical accuracy and process integrity.

In an increasingly competitive environment, accreditation by recognised industry bodies can help ifferentiate healthcare institutions. Such accreditation can also have reputational and commercial benefits in the context of empanelment under insurance programs, eligibility for public tenders, and participation in government health schemes.

VII. Legal liability of healthcare establishments in India

Compliance with licensing conditions and professional standards should not be treated as mere procedural requirements by healthcare establishments. Clinical establishments and healthcare service providers may be subject to extensive penalties, license revocation or disciplinary action in case of non-compliance, underscoring the necessity to implement robust compliance protocols, practitioner vetting mechanisms, and effective incident response systems.

A. Statutory penalties and licence revocation for non-compliance

Pursuant to the CE Act and similar state-specific enactments governing clinical establishments, healthcare establishments found to be in breach of registration conditions may face strict enforcement measures. Appropriate authorities are empowered to issue show-cause notices under the CE Act and impose financial penalties ranging from INR 10,000 to INR 5,00,000, depending on the nature and frequency of the non-compliance. In serious cases, the appropriate authorities are empowered to cancel the registration of clinical establishments, thereby effectively barring them from operation. The recent order by the Maharashtra government for cancellation of the registration of 258 private hospitals on account of violation of the Bombay Nursing Homes Registration Act, 1949 62 serves as a stark reminder of the potential consequences of non-adherence to compliance requirements by clinical establishments.

The conduct of medical practitioners falls within the jurisdiction of the respective State Medical Councils (SMCs) at the state level and the National Medical Commission (NMC) at the central level. These statutory bodies constituted under relevant state or central laws regulate the conduct of registered medical practitioners. SMCs and the NMC possess the authority or revoke medical to suspend licences in case medical negligence or ethical/professional misconduct. 63 Recent orders issued by the Gujarat Medical Council suspending 4 specialist doctors for malpractice and negligence, 64 indicate the preparedness of medical councils to take disciplinary action against errant doctors found in breach of professional standards.

B. Civil Liability and Consumer Protection for Patients

Hospitals and healthcare providers may also be exposed to civil liability pursuant to the provisions of consumer protection laws. The Supreme Court of India in its landmark decision in Indian Medical Association vs. V. P. Shantha, 65 stated that service rendered to a patient by a medical practitioner (except where the doctor renders service free of charge to every patient or under a contract of personal service), by way of consultation, diagnosis and treatment, both medicinal and surgical, would fall within the ambit of ‘service’ as defined under the Consumer Protection Act, 1986. More recently, the Bombay High Court, in Medicos Legal Action Group v. Union of India 66 has clarified that healthcare services continue to be covered within the definition of “service” under the new Consumer Protection Act, 2019 also. This permits patients to pursue remedies for medical negligence, misdiagnosis, inadequate facilities and billing irregularities before consumer disputes redressal commissions.

Consumer forums have, in several instances, demonstrated a proactive stance by awarding compensation as a civil remedy for the harm suffered by patients. For instance, in a recent case, the Jalandhar District Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission directed Care Max Super Speciality Hospital and 3 of its doctors to pay INR 5,00,000 as compensation for misrepresentation and negligence in treating a patient suffering from acute inferior wall myocardial infarction.67 This highlights that healthcare providers are not only responsible for ensuring compliance with licensing requirements but may also be liable to monetarily compensate patients in case of breach of duty of care.

VIII. Environmental Safety

Healthcare facilities in India, in the course of providing medical services, generate various waste products that, if not managed appropriately, can pose significant environmental and public health risks. India has a robust regulatory regime governing environmental safety and waste management which will apply to the different types of waste which may be generated by a healthcare facility. The key legislations in this regard include:

A. Biomedical Waste Management Rules, 2016 (“BMW Rules”)

The BMW Rules apply to all entities which generate, collect, receive, store, transport, treat, dispose, or handle biomedical waste in any form, including specifically hospitals, nursing homes, clinics, dispensaries, pathological laboratories, blood banks, health care facilities and clinical establishments. 68 Every healthcare facility (in their capacity as an occupier of their relevant premises), irrespective of scale, must obtain authorization under the BMW Rules from the relevant state pollution control board (“SPCB”).

The BMW Rules set out the duties which are applicable to healthcare facilities as occupiers of bio- medical waste generating premises. It mandates occupiers to ensure that bio-medical waste is segregated at the point of generation in accordance with the prescribed colour-coded system. 69 Further, laboratory waste, microbiological waste, blood samples and blood bags are required to pre-treated through disinfection/sterilised by the occupier. 70 Where a common bio-medical waste treatment facility is available within 75 kilometres, healthcare facilities are prohibited from establishing on-site treatment and disposal facilities, however if such common bio-medical waste treatment facility is unavailable, on-site treatment facility is permitted to be established with prior approval of the SPCB.

Healthcare facilities are also required to ensure occupational safety of all persons handling bio- medical wastes and to conduct annual health checkups for all such persons. 71

B. Hazardous and Other Wastes (Management and Transboundary Movement) Rules, 2016 (“HM Rules”)

Due to the nature of their operations, healthcare facilities may generate hazardous waste (other than bio-medical waste), such as used chemicals, contaminated cotton rags and discarded cleaning materials. The occupiers of all facilities generating and/or storing hazardous waste are required to obtain authorization under the HM Rules from the SPCB. 72 An occupier is permitted to store hazardous waste on its premises up to 90 days, 73 but is required to ensure that the hazardous waste so generated is disposed in an authorised waste disposal facility thereafter. 74

C. Water and Air Pollution Control Acts

Pursuant to the provisions of the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974 and the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981, facilities discharging sewage / effluents or operating within designated air pollution control areas must obtain necessary consents from the SPCB. Practically, the licensing mechanism works in a two-fold manner—first, the consent to establish (CTE) must be obtained prior to commencing establishment of the healthcare facility (say a hospital or nursing home), and second, the consent to operate (CTO) must be obtained post establishment of the facility but before commencing operations. Health care facilities (as defined under the BMW Rules) may be designated as green, orange or red category industries, depending on the number of beds or the presence of an incinerator in the premises, and the corresponding pollution index score.75

Red category health care facilities are the most strictly regulated, followed by orange and then green category facilities.

D. Other environmental compliances

Apart from the abovementioned licenses, depending on the nature of operations undertaken, certain other environmental compliances may apply to a healthcare facility, including pursuant to the provisions of the Atomic Energy (Safe Disposal of Radioactive Wastes) Rules, 1987, the E-Waste Management Rules, 2016, the Battery Waste Management Rules, 2022, and the Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016.

IX. Digital Healthcare and Data Privacy

India’s regulatory landscape for healthcare facilities is rapidly evolving in response to digital health technologies. Digital health in India encompasses a broad array of innovations, ranging from telemedicine to AI-powered diagnostics and mobile health apps. Efforts are underway to integrate these innovations within existing legal frameworks to effectively address emerging legal challenges surrounding patient safety, data protection, and liability.

A. Regulations of digital health offerings

India’s digital health ecosystem has emerged as one of the fastest-growing segments of the healthcare market, encompassing e-pharmacies, telemedicine, and health-tech platforms. India has experienced significant growth in the e-pharmacy segment, with the market valued at USD 3.18 billion in 2024, and projected to grow to USD 12.71 billion by 2033.76 In the absence of dedicated legislation, regulatory oversight over e-pharmacies currently flows from the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940 (“D&C Act”), the Drugs and Cosmetics Rules, 1945 (“D&C Rules”), and the

Pharmacy Act, 1948, supplemented by applicable e-commerce and data protection laws. The office of the Drugs Controller General of India (DCGI) has clarified that the D&C Act does not differentiate between conventional (physical) pharmacies and online pharmacies; accordingly, licensing authorities are expected to take stringent action against such persons involved in online sale of drugs in violation of the provisions of the D&C Act.77

E-pharmacies are therefore technically required to comply with the same obligations as physical pharmacies, including obtaining valid licences (retail drug licence in Form 20/21 and wholesale drug licence in Form 20B/21B under the D&C Act), employing registered pharmacists and verifying prescriptions. However, various e-pharmacy platforms have contended that they are not bound by the requirements under the D&C Act as they are merely aggregator platforms which act as intermediaries between interested users and licensed pharmacies.78 Consequently, the regulation of e-pharmacy platforms remains a legal grey area. While the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare had framed draft rules for the governance of e-pharmacies back in 2018,79 and the proposed Drugs, Medical Devices and Cosmetics Bill, 2023 also contemplated framing of rules for the licensing and manner of online sale of drugs,80 no specific regulations directly addressing the operations e-pharmacies have yet been formally enacted.

The Indian telehealth sector is also emerging as a valuable contributor to the Indian economy with an estimated value of USD 3.87 billion in 2025 and projected growth of USD 9.75 billion by 2030. 81 The Telemedicine Practice Guidelines, 2020 (“Telemedicine Guidelines”) forming part of the Indian Medical Council (Professional Conduct, Etiquette and Ethics Regulation, 2002) is the chief legislation governing telemedicine practice in India. It permits registered medical practitioners to offer consultations through telecommunication methods, 82 subject to adherence to prescribed standards regarding doctor and patient identification, patient consent, privacy and confidentiality, and prescription of drugs. 83 In line with the D&C Act and the D&C Rules, the Telemedicine Guidelines outlines restrictions in relation to the category of drugs which may be prescribed depending on the mode and the type of teleconsultation and even sets out the model form of prescription. While the Telemedicine Guidelines represent the evolution of the regulatory framework corresponding to developments in the healthcare sector, it remains limited in its scope as it regulates only the conduct of registered medical practitioners on telemedicine platforms but not the operation of the telemedicine platforms themselves. Accordingly, there is a need for further regulatory guidance to clearly delineate the roles and responsibilities of telemedicine platforms in India.

B. Data Privacy Regulations

Unlike various other jurisdictions, India does not currently have a dedicated legislation governing the protection of health-related data. Digitally collected or collated healthcare information is currently governed by the Information Technology Act, 2000 (“IT Act”) and the Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011 (“SPDI Rules”). The Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023, once brought into effect, will form the overarching governing law in relation to data privacy, including healthcare data.

The SPDI Rules categorise “physical, physiological and mental health condition” and “medical records and history”, as sensitive personal data or information (“SPDI”), 84 and seeks to safeguard such SPDI by requiring body corporates collecting and storing SPDI to obtain written consent from providers of SPDI, 85 formulate and publish privacy policies, 86 and implement secure data practices. 87 The IT Act provides for levy of compensatory damages on body corporates that fail to implement reasonable security practices in line with the SPDI Rules while handling sensitive personal data, resulting in wrongful loss or gain to any person.88 However, given the large scale incidents of data breach targeting healthcare data, 89 concerns regarding data privacy remain at large.

X. Conclusion

India’s healthcare sector is undergoing rapid transformation and exponential growth, presenting a significant challenge for the regulatory framework to evolve at pace, balancing public interest with the technological innovation. For both investors and healthcare providers, ensuring compliance with the complex array of central and state healthcare laws is essential to establish credibility and obtain sustained growth in the Indian market. However, state level variations in regulatory requirements as well as ambiguities in application of laws, particularly in relation to new-age, innovative health-tech ventures, pose considerable challenges to the survival of enterprises within this highly regulated sector. With this background, organisations and investors in India’s healthcare sector need to view regulations as a foundation for responsible growth, rather than as hurdles. To succeed in the Indian regulatory environment, healthcare organisations must embed legal compliance, governance, and data protection into the fabric of their operations, while maintaining their focus on patient safety. By aligning their business practices with existing regulatory frameworks, safeguarding patient rights, and addressing state-specific compliance nuances, healthcare providers and investors alike can look to mitigate risk and create long-term value for their respective stakeholders.

Authors: Puneet Shah (Partner), Amrita Ghosh (Senior Associate) and Kaumudi Sharma (Associate) are part of the Private Equity and Venture Capital team at the Mumbai office.

About Us: At IC RegFin Legal (formerly practicing under the brand IC Universal Legal/ ICUL), our core philosophy revolves around helping our clients accomplish their business and strategic objectives. This philosophy is built upon a foundation of extensive legal and regulatory expertise, coupled with a profound understanding of the ever-evolving market and economy. The Private Equity and Venture Capital team has a proven track record of advising esteemed clients and is committed to delivering high quality legal services aligned with our clients’ goals. Our in-depth legal knowledge, sector experience, and multidisciplinary approach enable us to provide effective and comprehensive solutions in the venture capital, private equity, and merger & acquisition space.

Disclaimer: This document has been created for informational purposes only. Neither IC RegFin Legal (formerly practicing under the brand IC Universal Legal/ ICUL) nor any of its partners, associates, or allied shall be responsible/liable for any interpretational issues, incompleteness/inaccuracy of the information contained herein. This document is intended for non-commercial use and the general consumption of the reader and should not be considered as legal advice or legal opinion of any form and may not be relied upon by any person for such purpose.

1 Reghu Balakrishnan, ‘PE fund KKR closes third buy in Kerala, at Meitra Hospital’, The Economic Times (September 22, 2025), https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/banking/finance/pe-fund-kkr-closes-third-buy-in-kerala-at-meitra- hospital/articleshow/124032540.cms?from=mdr (Last accessed on October 6, 2025); M. Sriram, ‘Blackstone enters Indian healthcare services with Care Hospitals buy’, Reuters (October 30, 2023), https://www.reuters.com/markets/deals/blackstone-enters-indian-healthcare-services-with-care-hospitals-buy-2023-10-30/ (Last accessed on October 6, 2025).

2 EY, ‘PE/VC Investments in India reach US$13.7 billion across 284 deals in 1Q 2025: EY-IVCA Report’, EY India (April 21, 2025), https://www.ey.com/en_in/newsroom/2025/04/pe-vc-investments-in-india-reach-us-dollor-13-point 7-billion- across-284-deals-in-1q-2025 (Last accessed on October 6, 2025).

3 ‘Big money is making a beeline for Indian hospitals’, The Economic Times (ET Online, June 30, 2025), https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/healthcare/biotech/healthcare/big-money-is-making-a-beeline-for-indian- hospitals/articleshow/122156400.cms?from=mdr (Last accessed on October 6, 2025).

4 ‘World Health Day: India’s healthcare sector reflects 12.59 per cent growth in 2024-25’, The Economic Times (April 7, 2024), https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/healthcare/biotech/healthcare/world-health-day-indias-healthcare-sector-reflects-12-59-per-cent-growth-in-2024-25/articleshow/109105006.cms?from=mdr (Last accessed on October 6, 2025).

5 Government of India, ‘Notes on Demands for Grants, 2025–2026: No. 46’, Department of Health and Family Welfare (India Budget, July 2025).

6 ‘India’s Medical Value Travel market projected to reach $13.42 billion by 2026’, Business Standard (February 4, 2025),https://www.business-standard.com/markets/capital-market-news/india-s-medical-value-travel-market-projected-to-reach-13-42-billion-by2026 125020401361_1.html (Last accessed on October 6, 2025).

7 Karan Singh, Parijat Ghosh Dr Debasish Talukdar, ‘India Healthcare Roadmap for 2025’, Bain & Company (Brief), https://www.bain.com/insights/india-healthcare-roadmap-for-2025-brief/ (Last accessed on October 6, 2025).

8 Aditya Srivastava, ‘Preventive Healthcare: The New Frontier in India’s Health Revolution’, Kalaari Capital (July 22, 2024), https://kalaari.com/preventive-healthcare-the-new-frontier-in-indias-health-revolution/ (Last accessed on October 6, 2025).

9 Bain & Company, ‘Healthcare Innovation in India’ Bain & Company, (Insight, March 2024), https://www.bain.com/insights/healthcare-innovation-in-india/ (Last accessed on October 6, 2025).

10 Aneeka Chatterjee, ‘Pvt hospitals expand tele-ICUs network as critical care demand grows’, Business Standard (August 29, 2024), https://www.business-standard.com/industry/news/pvt-hospitals-expand-tele-icus-network-as-critical-care-demand-grows-124082900956_1.html (Last accessed on October 6, 2025).

11 Ayanti Bera, ‘Health-tech investors look beyond e-pharmacy, diagnostics’ The Financial Express, (October 5, 2024),

https://www.financialexpress.com/business/healthcare-health-tech-investors-look-beyond-e-pharmacy-diagnostics-3630950/ (Last accessed on October 6, 2025).

12 Rupali Mukherjee, ‘Hospitals garner 50% share in healthcare FDI’, The Times of India (December 5, 2024),https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/hospitals-garner-50-share-in-healthcare-fdi/articleshow/115985131.cms (Last accessed on October 6, 2025).

13 KPMG, From Volume to Value: Fostering research and innovation in India’s medical device industry, (October 2023),

https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/in/pdf/2023/10/from-volume-to-value.pdf (Last accessed on October 6, 2025).

14 Paragraph 1.2, Annex 6, Master Direction – Foreign Investment in India (Updated as on January 20, 2025).

15 Ministry of Finance, ‘Updated Harmonized Master List of Infrastructure Sub-sectors’, Department of Economic Affairs (October 13, 2014).

16 Paragraph 1.3, Annex 6, Master Direction – Foreign Investment in India (Updated as on January 20, 2025).

17 List II, Seventh Schedule, Constitution of India.

18 List III, Seventh Schedule, Constitution of India.

19 Section 2(c), Clinical Establishments (Registration and Regulation) Act, 2010.

20 Section 1(4)(a), West Bengal Clinical Establishments (Registration, Regulation and Transparency) Act, 2017.

21 Sections 23 and 30(2), Clinical Establishments (Registration and Regulation) Act, 2010.

22 Section 5(2), Maharashtra Nursing Homes Registration Act, 1949; Section 5(2), the Delhi Nursing Homes Registration

Act, 1953.

23 Sections 16(6) and 17, Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Act, 2021.

24 Rules 16.4 and16.5, Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Rules, 2022.

25 Sections 2(1)(e) and 2(1)(u), Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Act, 2021.

26 Section 21(g), Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Act, 2021.

27 Section 21, Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Act, 2021 read with Rule 25, Assisted Reproductive, Technology (Regulation) Rules, 2022.; Rules 10, 11 and 14 read with Schedule I, Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Rules, 2022.

28 Section 22(1)(a), Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Act, 2021.

29 Section 22(4), Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Act, 2021.

30 Section 22(1)(b), Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Act, 2021.

31 Section 28, Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Act, 2021.

32 Sections 26 and 32, Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Act, 2021.

33 Section 11, Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021 read with Rules 10 and 11, Surrogacy (Regulation) Rules, 2022.

34 Sections 3 and 4(ii), (iii), Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021.

35 Section 8, Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021.

36 Section 6(2), Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021.

37 Section 7, Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021.

38 Section 10, Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021.

39 Rule 8, Surrogacy (Regulation) Rules, 2022.

40 Rule 6, Surrogacy (Regulation) Rules, 2022.

41 Rule 5, Surrogacy (Regulation) Rules, 2022.

42 Rule 5(2), Surrogacy (Regulation) Rules, 2022.

43 Sections 2(o) and 3A, Pre-conception and Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection) Rules, 1996.

44 Rule 3A, Pre-conception and Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection) Rules, 1996.

45 Rules 7 and 8, Pre-conception and Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection) Rules, 1996.

46 Rule 3, Pre-conception and Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection) Rules, 1996.

47 Rule 13, Pre-conception and Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection) Rules, 1996.

48 Section 4, Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971.

49 Rule 5, Medical Termination of Pregnancy Rules, 2003.

50 Adsa Fatima & Sarojini Nadimpally, ‘Abortion Law in India: A Step Backward After Going Forward’, Supreme Court

Observer (November 17, 2023), https://www.scobserver.in/journal/abortion-law-in-india-a-step-backward-after-going-forward/ (Last accessed on October 6, 2025).

51 Ruel 3B, Medical Termination of Pregnancy Rules, 2003.

52 Section 3(2), Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971.

53 Andhra Pradesh Transplantation of Human Organs Act, 1995.

54 Sections 14 and 14A, Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Act, 1994.

55 Sections 11 and 19, Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Act, 1994.

56 Section 3, Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Act, 1994.

57 Section 5, Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Act, 1994.

58 Section 9(1), Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Act, 1994.

59 Section 9(3), Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Act, 1994.

60 Rule 3, Atomic Energy (Radiation Protection) Rules, 2004.

61 Rule 9, Atomic Energy (Radiation Protection) Rules, 2004.

62 Faisal Malik, ‘State orders closure of 258 pvt hosps over violations’, Hindustan Times (July 18, 2025),https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/mumbai-news/state-orders-closure-of-258-pvt-hosps-over-violations-101752780027844.html (Last accessed on October 6, 2025).

63 Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, ‘Regulating Practitioners Through Medical Councils’, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy(December19,2023),https://vidhilegalpolicy.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Professional_Regulation_through_Medical_Councils_12_single_page.pdf(Last accessed on October 6, 2025).

64 ‘Licences of 4 doctors suspended for malpractice and negligence’, Times of India (August 23, 2024),https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/ahmedabad/licences-of-4-doctors-suspended-for-malpractice-and-negligence/articleshow/112723074.cms (Last accessed on October 6, 2025).

65 (1995) 6 SCC 651.

66 2021 SCC OnLine Bom 3696.

67 Yakshi Chugh, ‘PGDCC Holder treats heart patient, Hospital, Doctors Fined Rs 5 Lakh’, Medical Dialogues (April 10, 2025),https://medicaldialogues.in/mdtv/channels/healthshorts/pgdcc-holder-treats-heart-patient-hospital-doctors-fined-rs-5- lakh-146417 (Last accessed on October 6, 2025).

68 Rule 2, Biomedical Waste Management Rules, 2016.

69 Rule 4(b), Biomedical Waste Management Rules, 2016.

70 Rule 4(c), Biomedical Waste Management Rules, 2016

71 Rules 4(l) and (m), Biomedical Waste Management Rules, 2016.

72 Rule 6(1), Hazardous and Other Wastes (Management and Transboundary Movement) Rules, 2016.

73 Rule 8(1), Hazardous and Other Wastes (Management and Transboundary Movement) Rules, 2016.

74 Rule 4(4), Hazardous and Other Wastes (Management and Transboundary Movement) Rules, 2016.

75 Central Pollution Control Board, ‘Classification of Sectors into Red, Orange, Green, White and Blue Categories’ (January 2025).

76 IMARC Group, ‘India Online Pharmacy Market Size, Share, Trends and Forecast by Medicine Type, Platform Type, Product Type, and Region, 2025-2033’, IMARC Group (2025), https://www.imarcgroup.com/india-online-pharmacy-market (Last accessed on October 6, 2025).

77 Office of Drugs Controller General (India), Notice bearing reference no.7-5/2015/Misc/(e-Governance)/091 (December 30, 2025).

78 Rajya Sabha, Unstarred Question No. 2205, Answer by Dr. Bharati Pravin Pawar (erstwhile Minister of State in the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare) on the query posed on the status on e-pharmacy platforms (August 8, 2023).

79 Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Draft Drugs and Cosmetics (Amendment) Rules, 2018 (28 August 2018), G.S.R.

817(E).

80 Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Drugs, Medical Devices and Cosmetics Bill, 2023.

81 Mordor Intelligence, ‘India Telehealth Services Market: Size, Share, Trends & Forecast, 2025-2030’ (2025),https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/telehealth-services-market-in-india(Last accessed on October 6, 2025).

82 Guideline 1.3, Telemedicine Practice Guidelines, 2020.

83 Guidelines 3.2, 3.4, 3.7, Telemedicine Practice Guidelines, 2020.

84 Rule 3, Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011.

85 Rule 5(1), Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011.

86 Rule 4, Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011.

87 Rule 8, Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011.

88 Section 43A, Information Technology Act, 2000.

89‘Personal data of about 3 crore Star Health customers up for sale online, hacker alleges; top official for breach’, The Hindu(October 10, 2024), https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/technology/personal-data-of-about-3-crore-star-health-customers-up-for-sale-online-hacker-alleges-top-official-for-breach/article68739263.ece (Last accessed on October 6, 2025).